Showing posts with label Girl Shy. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Girl Shy. Show all posts

Thursday, August 10, 2017

The actor: Harold Lloyd's reaction shots

A memorable Harold Lloyd reaction shot from Girl Shy. Harold plays a yokel whose book "How to Make Love" has just been rejected by a publisher as ridiculous and worthless. But his expression isn't a reaction to that humiliation. This was his one chance to win a very wealthy girl he has fallen in love with, and that dream has just turned to dust.

This scene proves what Hal Roach famously said: "Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the best actor playing a comedian who ever lived." Any dramatic actor would be hard-pressed to sustain scenes of emotional distress with such skill.

He himself didn't think he was very funny, but he could "do" funny superbly. His pathos never turned to bathos, as sometimes happened with Chaplin (whose films are much more dated than Harold's). And as Roach said, Harold was a plausible leading man whose romantic quests weren't vaguely creepy or driven by pity.

Harold didn't wear a clown suit or pull faces or do any of the things silent comics did to get a laugh. He was an ordinary person caught up in extraordinary circumstances, and his complete inability to cope brought the audience on-side like nothing else. But when he triumphed in the end, all of our own failed fantasies were brilliantly realized.

And one more thing - he always got the girl.

Sunday, November 13, 2016

Harold Lloyd: Ride of the Valkyries

Another of my incongruous attempts to glom classical music onto scenes from Harold Lloyd. It almost works, in this case. This is the race to the church from Girl Shy set to Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

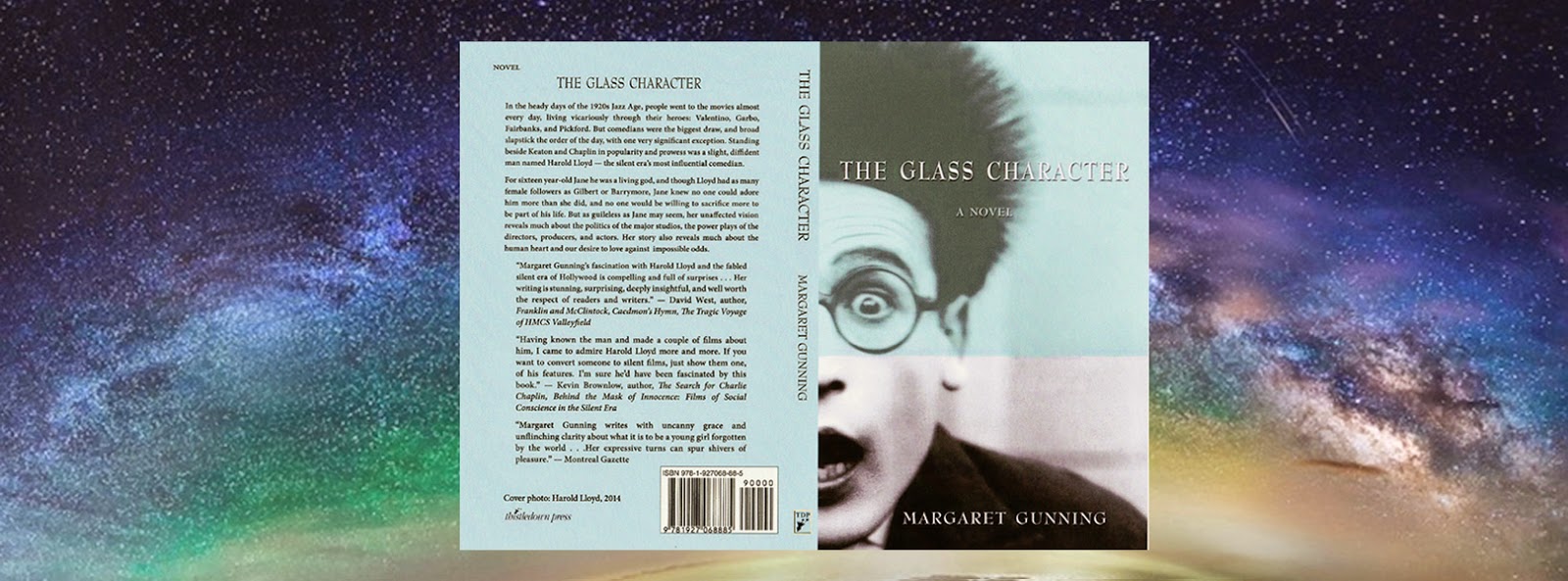

Writers have their hearts ripped out

Since I finally figured out how to use the video camera, mainly to photograph all the wildlife in the back yard, I'm experimenting with other stuff, mainly ads for my doomed novel, The Glass Character. Maybe I'll have fun with it; maybe I won't. I like the idea of the screen beside me, and the fact these are silents means I can blather on as much as I want. I know what it is to be rejected (stomped into the ground a few hundred times?), so this scene spoke to me in particular.

Tuesday, July 9, 2013

Saturday, July 6, 2013

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

Harold Lloyd: you can't keep a good man down

Drink was, in fact, the curse of the family. Mildred (or “Mid”, or “Molly”, as Lloyd called her) had been an alcoholic from some time in the forties, when it is said she wanted desperately to divorce Lloyd. In her late years a full-time nurse was employed mainly to see that her perfume bottles did not mysteriously get filled with booze, that her habit of drinking Listerine did not get out of hand. In a pathetic family – “a disaster”, as even Lloyd’s kindly friend Simonton put it – she was perhaps the most pathetic member. One thinks of her – never a very mature, forthcoming or stimulating person – wandering the halls of the great house, her husband either absent or preoccupied by one of his interests, her children all gone, and none of them bearing her any very kind feelings, caring mainly for her two companionable poodles and her booze, and one sees the end results of the flaws that, almost from the first, people had detected in Lloyd’s art – its abstractness, its mechanical quality, its lack of real warmth. It is all dreadfully sad.

Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter, 1974

This was one of the more disturbing passages I found in my relentless quest for information about Harold Lloyd. In fact, this whole book sells Lloyd short in just about every facet of his life, but never is it more hurtful than in this personal attack on his family.

One wonders, in fact, if he knew or cared about the surviving members of Lloyd's family, about their feelings for him. He seems to have assumed no one was left who cared two figs about him, or if they did, that they weren't significant enough to merit a modicum of respect.

At the same time, this critic - and I don't name him to cover MY ass, not his! - is one of those unassailable figures in "cinema" (a step up in snobbishmess even from "film") whom no one ever really questions. Even to this day, his work is hugely influential. What puzzles and offends me almost as much as his nasty cracks at his family is his description of Lloyd's art: "its abstractness, its mechanical quality, its lack of real warmth."

I did find out some things about Harold Lloyd and his family, in particular from a more recent bio written by silent film historian Jeffrey Vance in collaboration with Harold Lloyd's granddaughter (whom he raised), Suzanne Lloyd. The book is honest and forthright about the sometimes-serious problems the family had; it was hardly a snow job. But as with most families, the dynamics were complicated, and joy and celebration often ran neck-in-neck with sorrow. To call Lloyd's home life "dreadfully sad" is to miss the point.

Alcoholism is a family pattern, with stubborn roots deeply buried in the soil of generations. Though Harold did not drink, some of those around him did, and it inevitably did them harm. But it's absurdly unlikely that his former leading lady Mildred Davis spent her final years wandering around the halls of their mansion like a ghost. Moreover, "it is said" does not pass as a particularly reliable source of information, and in fact can often mean nothing at all. It's as bad as that godawful phrase "studies show", which too many people seem to swallow without question.

I wasn't there, so I don't know exactly how things were at Greenacres, but I honestly don't think they were anything like this. I do know that the word "mechanical" stuck to Lloyd's films for decades, mainly because people seemed to take this critic's word as gospel. It did irreparable harm for decades and kept his movies buried for far too long.

There's a Lloyd revival going on, thank God, which proves that these descriptions are inadequate and highly inaccurate. In his Everyman's search for love (which is at the core of most of them), Harold Lloyd invented a new genre: the romantic comedy. It could even be argued that he broke ground in screwball comedy with the delightfully wacky Why Worry? I haven't seen every Lloyd film, but I've seen as many as I can get my hands on. The features he made after 1920 are nuanced and three-dimensional. His Glass Character tugs at the heart. But since that cold, abstract label was pinned on him shortly after his death and his work was either unavailable to the public or adulterated practically beyond recognition, it was accepted in the movie world without a lot of question.

When Time-Life Films, which will be re-releasing most of Lloyd's films over the next four years, invited me to attempt this critical-biographical sketch of the comedian, it had already commissioned a veteran correspondent of the Time-Life News Service to interview as many friends, relatives and co-workers of Lloyd's as he could find. His remarkably thorough dispatches were placed at my disposal for this book, and it is a pleasure to acknowledge my indebtedness to him. I am sure he would like me to express gratitude to those who provided him information.

This means The Shape of Laughter (a bizarre title that basically means nothing) was not written from primary sources and in fact had "contractual obligation" written all over it. He simply took someone else's material, believed it without question, and wove it into a book. No doubt the correspondent's opinion of Lloyd's work, whatever it was, must have been mixed in to this rehash. It makes one wonder if Time-Life wanted the glossy seal and cache of this particular critic to boost book sales, even if he didn't really write the book. Or did he simply owe them one? Such things are known to happen, but if you ever raise it as a possibility, all hell breaks loose, along with a storm of vitriolic denial.

Two years after Lloyd died in 1971, Time-Life signed signed a distribution deal for his films and handled them with a tragic lack of understanding. The shorts were packaged with a commentary in the style of Pete Smith ("Poor Harold! It's doom for the groom unless he gets to his room!"), which effectively sank them without a trace. The features were spared the commentary, but insensitive, honky-tonk scores and the elimination of entire sequences often crippled their effect.

May I add to that the constant, annoying, ridiculously exaggerated sound effects?

In spite of all the factors that came together to compromise the integrity of Lloyd's work, it remained intact in the vault, sleeping, awaiting a second life. No one could have predicted the huge advances in film restoration that would strip the grey veils off his masterpieces and reveal them clean as new. No one could have predicted that Turner Classic Movies would get behind this renaissance, drawing more and more people back to pictures that are so vibrant and well-made that tired old comparisons to Chaplin and Keaton no longer apply.

Lloyd only "comes third" in some people's minds because they weren't there, and because they have had their viewpoint skewed by outdated, poorly-researched critical commentary. The best remedy for this is to buy the superb DVD movie set The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection and watch the hell out of them. I guarantee you, once you start, you won't ever be able to stop.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Wild about Harold: even more gifs!

From Girl Shy (Girl Shy, Girl Shy!)

In olden days, a glimpse of stocking. . .

. . . or is Harold stalking her?

I'd like to be that chair.

I've saved the best 'til last. . .

"You!"

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

The most romantic kiss in screen history!

The most romantic kiss in screen history. . . not Scarlett and Rhett. . . not Rick and Ilsa. . . not Bonnie and Clyde. . . but. . .

HAROLD AND JOBYNA!

Having written a novel about his life, a novel which I hope will find wings in the year 2013, I feel like I know Harold Lloyd personally sometimes, and I certainly know the course of his career. He probably made a couple hundred movies all-told, starting in 1917, but his classic films came out in the early-to-mid '20s. In rating his best pictures, most silent film buffs would probably name The Freshman (which is about . . . a freshman, a nerdy overaged college boy desperate for popularity) and Safety Last, in which safety comes last as Harold climbs up the side of a dizzyingly-tall building and hangs off the hands of a huge clock.

I like those, yes, love them in fact, and never tire of watching them (in fact I may watch them again tonight), but there is more pain and poignancy in The Kid Brother, and more still in Girl Shy, in which his characters are passive, even downtrodden youths who haven't yet discovered their manhood. This revelation/transformation always happens through love: Harold Lloyd's films are among the most romantic ever made, and none more romantic than my personal all-time favorite. . .

Why Worry?

This movie has the best title ever written, since it essentially means nothing and signals the fact that we are about to watch the very first screwball comedy. Never mind that the actual first screwball comedy would come out more than ten years later.

Against type, Harold plays a wealthy idler with all sorts of imagined ills who escapes to a tropical island with his gorgeous nurse (played by the sad-eyed, kewpie-lipped Jobyna Ralston). Said nurse is madly in love with Harold, who doesn't even seem to see her except in moments of unexpected contact: i.e., when she trips and falls into his lap as he sits in a totally unnecessary wheelchair. The slow-blooming smile on his face before he dumps her onto the ground communicates a subtle but very real sexual tension that will permeate the whole film.

She pines for him, he ignores her: it's the antithesis of practically every other Lloyd film, turning everything on its ear and releasing a madcap energy that outstrips anything in his other comedies. To add a little excitement, a dangerous anarchist plans a revolution on the island, causing all sorts of feverish violence that makes Harold exclaim, "You fellows must stop this. I came here for my health."

This shot illustrates one of the best Harold Lloyd gags ever: mountain-climbing up the side of a giant to try to remove his rotten tooth. (Never mind, you had to be there.) Wacky gag follows on wacky gag as Lloyd reaches a sort of fever pitch of brilliance and mad originality. At one point his nurse, dressed as a boy (a most unconvincing disguise) becomes furious with his self-centredness and hypochondria and begins to cuss him out as only one can in a silent movie. She's standing up, he's sitting, in the passive position, and once again that dreamy smile begins to play across his face before he tells her she has very beautiful eyes.

This comedy breaks every convention of the era, including the rule of the silent screen kiss: almost always quick, comedic, and preferably behind a screen. When Harold suddenly realizes he is madly in love with Jobyna, he doesn't just peck her but seizes her in his arms and kisses her with ferocious passion, something I've never seen in any other silent film, not even The Sheik. She resists for a second, then melts into his arms with a subtle leg-pop that conveys complete surrender.

How many takes were required to capture that volcanic kiss? I wonder. In any case, I envy Jobyna. There are murmurings that they were "involved", as he was involved with so many women in his lifetime. There was something seductive and bedroomy about his eyes (along with the canny intelligence and a touch of wildness) that was there for a lifetime.

And so: today, after literally years of searching, I've found a picture of that kiss! I can't find a video of it, I'm sorry, so you'll just have to watch the whole movie. Better yet, buy the DVD set, The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection, superbly remastered with charming, energetic scores by Robert Israel and Carl Davis.

Harold, Harold, you have basically ruined my life! I have probably gained 25 pounds because of you, due to all my fretting, my unproductive fuming. I need to tell your story so badly I ache with it. I KNOW I can do this, I feel it! I have it in me, I have the goods. And I'm not always this confident about my work.

What is it about a person who has the power to wreck your life from this distance? We were alive at the same time, yes, but he died when I was just a teenager. We were on the same planet together at the same time. Aieeeeeee! My heart! When will this hopeless yearning end?

SYNOPSIS: THE GLASS CHARACTER by Margaret Gunning

I would like to introduce

you to my third novel, The Glass

Character, a story of obsessive love and ruthless ambition set

in the heady days of the Jazz Age in the 1920s. This was a time when people

went to the movies almost every day, living vicariously through their

heroes: Valentino, Garbo, Fairbanks and Pickford. But comedians were the

biggest draw, and broad slapstick the order of the day - with one

very significant exception.

Standing beside Keaton and

Chaplin in popularity and prowess was a slight, diffident man named Harold Lloyd.

He hid his leading man good looks under white makeup and his trademark

black-framed spectacles. Nearly 100 years later, an iconic image of

Lloyd remains in the popular imagination: a tiny figure holding on for dear life

to the hands of a huge clock while the Model Ts chuff away 20 stories below.

With his unique

combination of brilliant comedy and shy good looks, Lloyd had as many female

followers as Gilbert or Barrymore. Sixteen-year-old Muriel Ashford, desperate

to escape a suffocating life under her cruel father's thumb, one day hops

a bus into the unknown, the Hollywood

While researching this

book, I repeatedly watched every Lloyd movie I could get my hands on. I was

astonished at his subtlety, acting prowess and adeptness at the art of the

graceful pratfall. His movies are gaining new popularity on DVD (surprisingly,

with women sighing over him on message boards everywhere!). The stories wear

well and retain their freshness because of the Glass Character's earnest good

nature and valiant, sometimes desperate attempts to surmount impossible

challenges.

Dear Sir or Madam, will you read my book

It took me years to write, will you take a look

Thursday, April 21, 2011

Do you call that thing a book?

I can't name a favorite Harold Lloyd movie. Like children or grandchildren, they're all special to me in their own way. But there is one in which Harold plays a character who is very close to my heart.

I watched Girl Shy again last night. I don't know what it is about this man: he was magical. Tender and fierce, brilliant and adorably clueless. He plays a tailor's assistant in a small town, a meek loner who can't even speak because of a debilitating stutter. By chance, he meets and wins the love of a beautiful rich girl with his sincerity and pure heart. But he has only one chance to make himself worthy of her: to become rich and famous as the author of a ludicrous guide to romance called The Secret of Making Love.

After being laughed and jeered out of the publisher's office, he does the only thing possible: sacrifices his own heart so that she will be spared the indignity of loving a pennyless loser. So he drives her away. He drives her away not just by taunting her, but by laughing at the very idea that they were ever in love. It is Lloyd's Pagliacci moment, the time when he must don the motley, play the clown, and break her heart for her own good. It is excruciating to watch, and one of those moments when Lloyd's extraordinary ability as an actor takes your breath away.

But the scene that really tears my heart out (can you guess why?) is that awful moment in the publisher's office, when he is briefly hopeful, then completely shattered. Social humiliation plays a large part in Harold Lloyd's universe, and he has an uncomfortable way of pulling his audience close and asking, "Has this ever happened to you?".

There is something in his eyes - his stunned, vulnerable, devastated eyes - the bottom suddenly dropping out of his world with a sickening gut-lurch, not because he won't be famous, but because he knows he will have to cut his girl loose, it's the only way to be fair to her - it's, what is it anyway? It's hard to watch, and the tension builds almost unbearably until the time when we can mercifully laugh again.

This is not mere comedy, folks, this is something else. This isn't the soppy melodrama of Chaplin or the can't-win fatalism of Keaton. Lloyd is a hopeful loser. And we so want him to win, we need him to win, for if we leave him in that terrible sinking vortex of failed dreams, we'll be reminded of things we don't want to recall.

But as always (and as in Lloyd's real life), Fate intervenes. In his darkest hour, tragedy is flipped over and transformed into a kind of acerbic comedy: the publisher suddenly decides to release his failed manuscript as a comic farce called The Boob's Diary. At first he rages and rails: they can't do this to me! It's undignified! Then, on reflection - and no doubt thinking of the girl - he reconsiders. . .

Ah, yes. The comprimise! (Has this ever happened to you?)

The most famous sequence in Girl Shy is the spectacular race to the church to prevent the rich girl from marrying a bigamist. I won't get into that now, as you should be watching it right this minute instead of reading about it, do you hear me? Get some Lloyd DVDs now, so you'll know what I'm talking about! If you don't, you're missing small masterpieces that tell stories that are not just humorous, but human.

The laughter in Lloyd comedies arises from an unlikely source, and it isn't just the ordinary fellow in extraordinary situations. It's from identification with a profound social dislocation. Harold so wants to belong, and doesn't, and can't, until he finally discovers, at the end of practically every movie, that there is only one person he needs to belong to. Because once he belongs to himself, you see, the girl is in the bag.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

+FRA.jpg)